http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Bickham-mid-rapid-UY-62-e1612397307108.jpg

1124

1500

chrispreperato

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/logo1.png

chrispreperato2021-02-03 04:50:002021-02-05 22:43:09The Learning Curve

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Bickham-mid-rapid-UY-62-e1612397307108.jpg

1124

1500

chrispreperato

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/logo1.png

chrispreperato2021-02-03 04:50:002021-02-05 22:43:09The Learning CurveThere were supposed to be a dam at Sang Run.

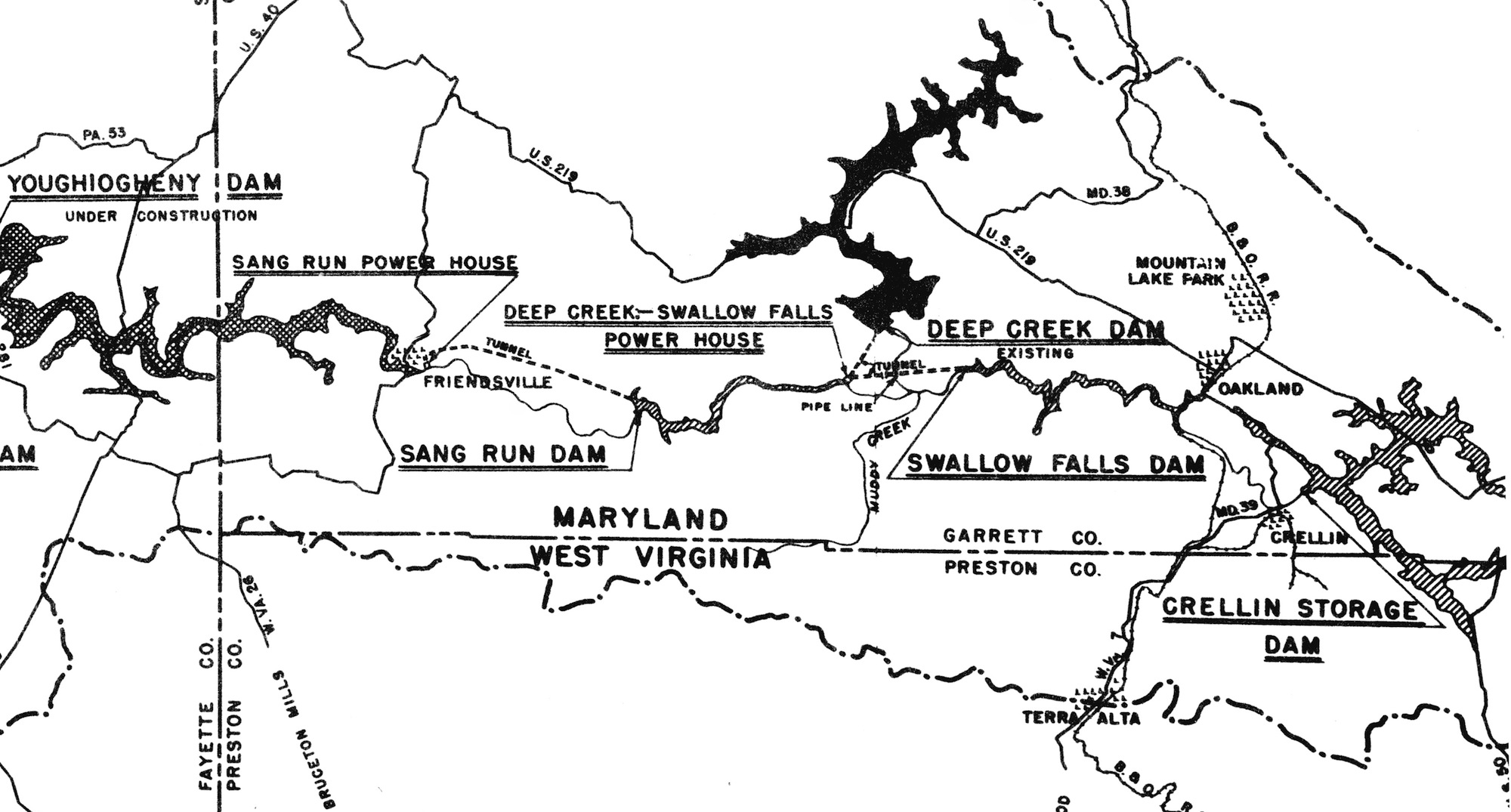

And another at Swallow Falls. A third major dam in Crellin for water storage would have completed the plan. The Youghiogheny flows free today from its origins above Silver Lake until it crosses the Pennsylvania border. But engineers, politicians, and power companies spent the first half of the twentieth century trying to reduce it to a series of lakes.

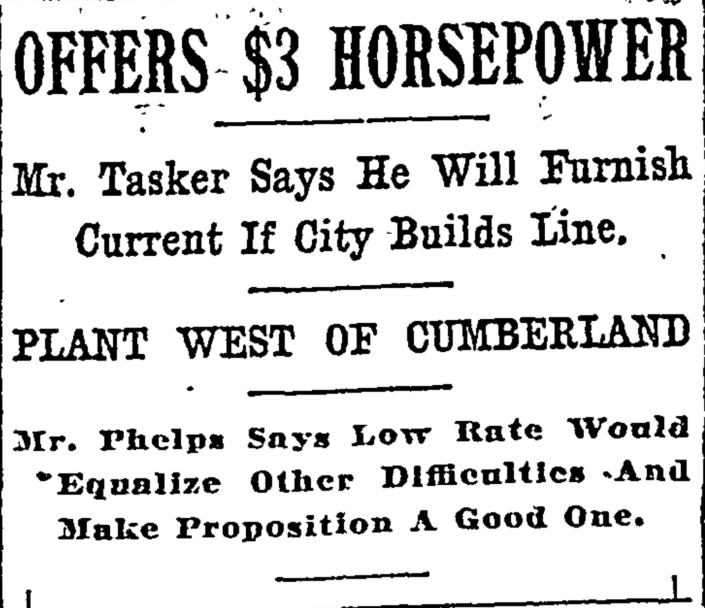

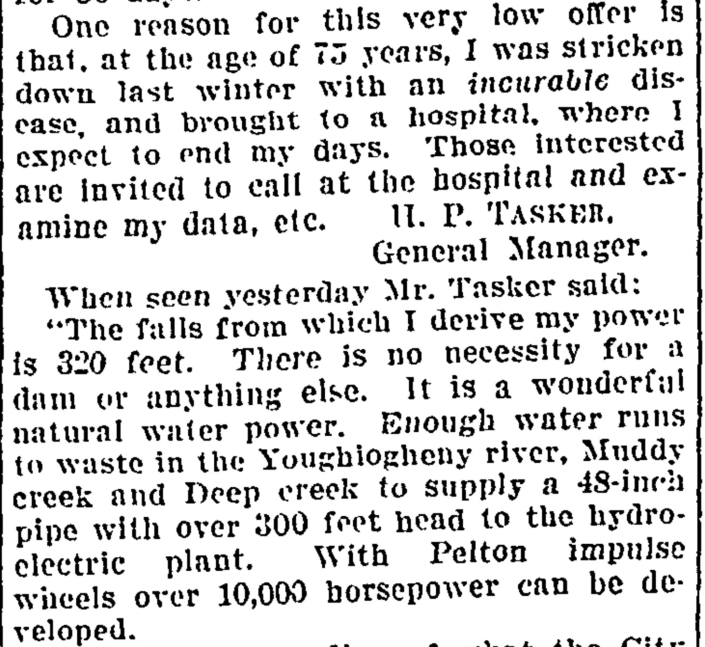

The most unique proposition came in 1910. The owner of the Youghiogheny Power and Light company proposed a centuries worth of cheap, renewable energy for Baltimore, MD. Stricken with an incurable disease at the age of 75, Mr H.P. Tasker decided he had a plan that would benefit society. With a ninety-nine year lease, and power offered at $3 per horsepower, all the city had to do was provide the transmission wires. More miraculously, he proposed doing so without building a single dam.

The rates he was proposing were “absurdly low,” and yet even under scrutiny of the city’s engineers, the plan held up. Even with the cost of transmission lines and property purchases for the right of way, the power paid for itself. And yet, like most hydro-electric plans in the Youghiogheny valley, nothing came of it. The same is true of a 1914 proposal that created the Youghiogheny Water and Power Company. A plan would come together, politicians would approve it, and the money would never materialize.

One of the marvels there is a tunnel which is being drilled straight through a mountain…The stupendous undertaking of this company is an engineer’s romance.

-The Baltimore Sun, July 10, 1924

In 1921, the Youghiogheny Hydro-Electric Company was given the right to build dams on Deep Creek and the Youghiogheny. They were the third company to be given the rights.

And like those previous companies, their surveyors found that building a series of dams (three on the Youghiogheny and one on Deep Creek) was the best course of action. But the demand for power had risen in the intervening years. They determined that building the dam on Deep Creek would be “economically self-sustaining.”

What followed was a months long process of buying up land titles and moving houses to higher ground. In total, 8,000 acres were purchased, including about 140 farms and 50 houses. They also had to relocate miles of highway and build new bridges across what would soon wider spans. Rail lines were extended to the dam, and temporary housing was built for the construction workers. A little over four years and $9 million later, the dam came online at 4:00pm on May 26th, 1925.

Ultimately, the Youghiogheny River in Maryland was saved by war.

In the midst of World War II, damming was no longer a private endeavor. The New Deal brought the federal government into the damming business, and the war made power a national security issue. Between the time Deep Creek Dam was built and the war began, power demand had risen 170% in Pittsburgh. Its growth during the 1940’s was exponential. With the steel foundation of the war machine being forged at the mouth of the Youghiogheny, the headwaters were called on once again to provide for those downstream.

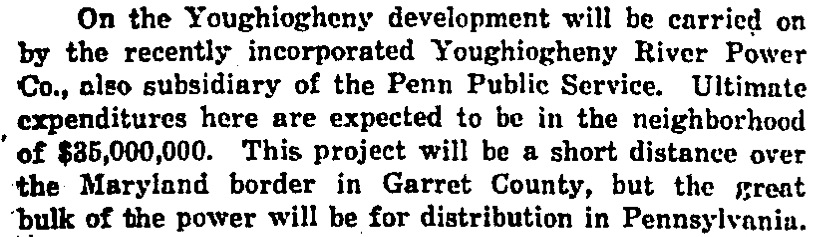

The Yough River Reservoir was already under construction in Confluence; approved earlier by the Flood Control Act of 1936. In addition to adding power generators to that dam, the familiar dams at Swallow Falls, Sang Run, and Crellin were back. This time, they were joined by two smaller dams. The first was the Victoria Dam on the Middle Yough, and the second was a re-regulation dam located below Bruner Run. At a cost of $38 million, they would provide 162,000 kilowatts of power. And with the federal government in charge, money was no longer an issue.

For those that had long viewed the Youghiogheny as “wasted water,” this plan was definitive and comprehensive. The dam in Crellin would finally tame the river at its source, and the remaining dams would firmly regiment the river’s path to Pittsburgh. The Yough would tumble through twelve miles of tunnels, its downhill rush harnessed by turbines for power; free flowing water foiled by concrete walls.

But building dams, much like fighting a war, requires resources. The bombing of Pearl Harbor occurred just five days before the Youghiogheny report was sent to Washington. At a time when the Hoover and Grand Coulee dams towered above the river banks, and the TVA was littering the American South with dams, the government couldn’t spare the resources to build the Youghiogheny dams. The men and equipment to build those dams were instead sent to build ships and tanks. The power to build planes and the atomic bomb came from larger dams out west. In a final twist of irony, the biggest and best plan to dam the Youghiogheny was simply too small to matter.

See More Upper Yough History

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Bickham-mid-rapid-UY-62-e1612397307108.jpg

1124

1500

chrispreperato

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/logo1.png

chrispreperato2021-02-03 04:50:002021-02-05 22:43:09The Learning Curve

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Bickham-mid-rapid-UY-62-e1612397307108.jpg

1124

1500

chrispreperato

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/logo1.png

chrispreperato2021-02-03 04:50:002021-02-05 22:43:09The Learning Curve

Cheesburger Falls

Lost and Found

Rapid Names

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Bickham-mid-rapid-UY-62-e1612397307108.jpg

1124

1500

chrispreperato

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/logo1.png

chrispreperato2021-02-03 04:50:002021-02-05 22:43:09The Learning Curve

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Bickham-mid-rapid-UY-62-e1612397307108.jpg

1124

1500

chrispreperato

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/logo1.png

chrispreperato2021-02-03 04:50:002021-02-05 22:43:09The Learning Curve http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Jack-Wright-at-National-19680729-copy-e1612411102473.jpg

659

880

chrispreperato

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/logo1.png

chrispreperato2014-11-06 03:27:482021-02-05 22:38:35Rapid Names

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Jack-Wright-at-National-19680729-copy-e1612411102473.jpg

659

880

chrispreperato

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/logo1.png

chrispreperato2014-11-06 03:27:482021-02-05 22:38:35Rapid Names