http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/charlieschoice-e1612397162104.jpg

349

466

chrispreperato

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/logo1.png

chrispreperato2021-02-03 04:59:582021-02-05 22:42:57Charlie’s Choice

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/charlieschoice-e1612397162104.jpg

349

466

chrispreperato

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/logo1.png

chrispreperato2021-02-03 04:59:582021-02-05 22:42:57Charlie’s ChoiceKendall is the name people remember.

But it wasn’t the first name of the little town a few miles above Friendsville, nestled tightly between the river and its canyon walls. Nor was it the second name of the once booming lumber hub; a production center along a rail-line that stretched as far south as Crellin, MD. Kendall was in fact the third name for the town, the one it died with. Today the name, and a few crumbling foundations are all that remain.

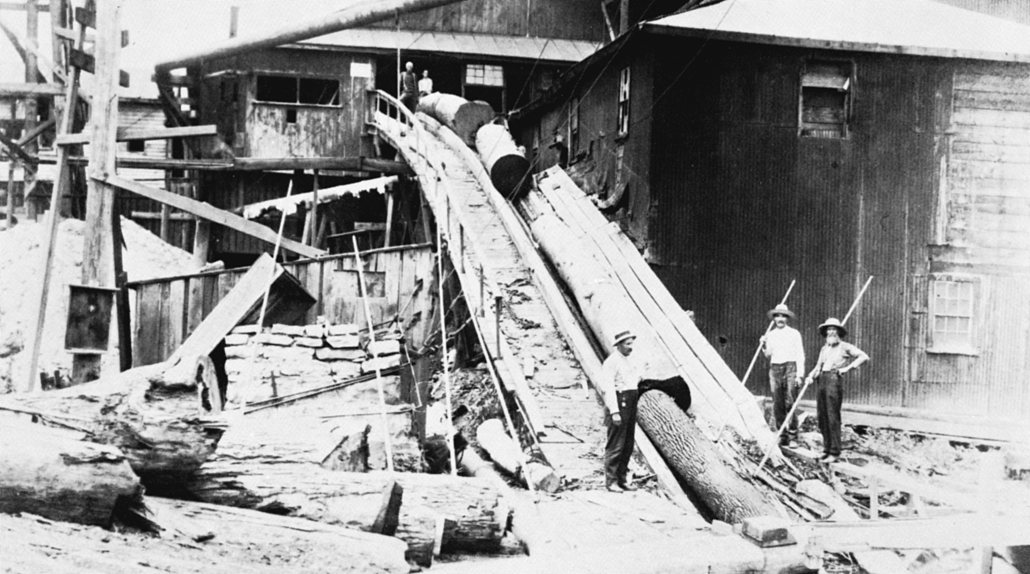

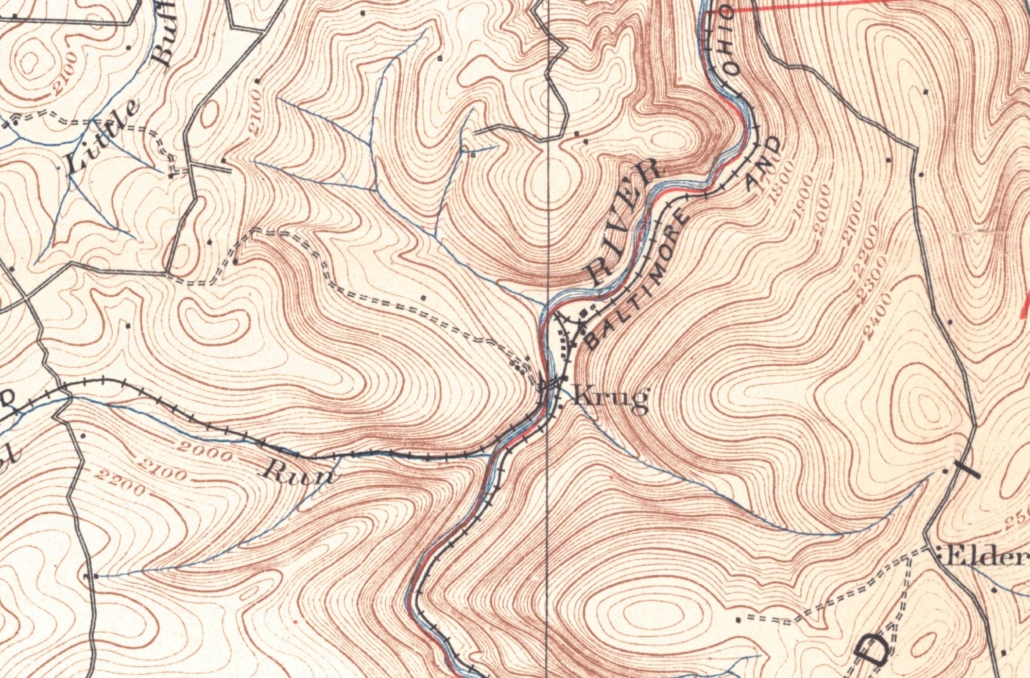

It began in November of 1889 as the town of Yough Manor. The lumber company of the same name decided to extend the Confluence-Oakland Railroad upriver from Friendsville to begin a milling operation. Two years later, the A. Knapp Company came in and set-up a stave mill. Shortly after, the town became Krug, MD, named for Henry Krug, one of the company officials. The mill and rail-line were expanded, as logging operations stretched further up the Youghiogheny Corridor. By the turn of the new century, the lumber industry in Garrett County employed nearly 1,000 people. The railroad itself followed closely along the river. The first bridge crossed in an area known to locals as “White Rock”, though today it’s better known as National Falls. A second crossing occurred where Salt Block Run enters on river left. Around 1909, the lumber company changed hands again. The Kendall Lumber Company, a large regional logging operation, purchased the mill and began working its way further upstream.

Superabundance was the myth of the day.

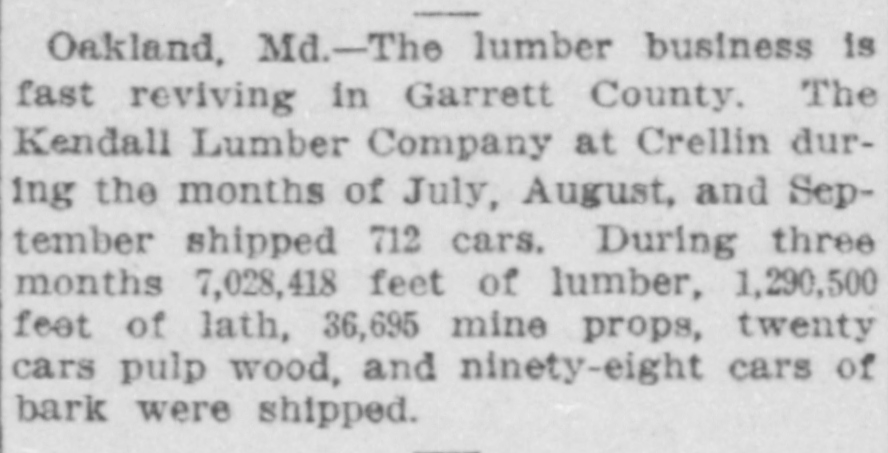

The idea that the world had more than enough resources for us to survive forever. And in resource rich Garrett County, that meant taking the land for all it had. The Kendall Lumber Company expanded to the area when it needed to increase its regional production. At the time of the purchase, Kendall Lumber Company was shipping out 3.5 million feet of lumber monthly.

And yet, even with that production, they were finding themselves millions of feet short, to the point of halting new contracts. They expanded their holdings throughout Mid-Atlantic, with the forests of the Yough Corridor becoming a piece of the puzzle.

But it’s not clear that the Youghiogheny Valley just north of Friendsville was ever all that productive. Steep banks meant that the output was lower than surrounding areas, and the hemlock forests meant lower prices. By the end of the 1910s, the Kendall Lumber Company had left the mill, selling it off to the McCullough Coal Mine Company. Shortly after, the houses and mill were torn down, and the railroad tracks were removed by the 1940s. Different industries took lumber’s place, and the forests began the long process of reclaiming what had been taken.

The legacy of Kendall appears a few miles downstream.

There the frenzied descent of the river is slowed to a crawl by the Youghiogheny River Dam. It’s construction in the early 1940’s was the result of a massive flood control project. With the headwaters cleared of trees, there was nothing to slow the surge of winter snow melt and spring rains. Annually, the river spilled over its banks and charged furiously to its convergence in Pittsburgh. Major floods in 1902, 1907, and 1912 still rank as the highest river peaks, but they pale in comparison to the flood of 1936.

Record rain fell on still melting snow, and nearly 500,000 cubic feet per second met at the junction of the three rivers. For a few days, Pittsburgh resembled Venice. One hundred thousand buildings were destroyed and the damage was estimated at $250 million ($4.3 billion today). To the citizens, and even members of Congress, it was clear that the city needed a solution for the annual rush of water. And so it turned, as it always has, upstream.

Dams. Dams were the solution. Far upstream, between the half empty hillsides, concrete walls could slow the rushing tide. Far from the mouth of the river, spring rains could be slowed before they even started to flow. Far from the minds of the people were the concerns of a half centuries abuse, of forests cut down to the stumps. Far from Pittsburgh, in a place where few people lived, it was acceptable for roads and houses to be buried beneath the water.

See More Upper Yough History

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/charlieschoice-e1612397162104.jpg

349

466

chrispreperato

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/logo1.png

chrispreperato2021-02-03 04:59:582021-02-05 22:42:57Charlie’s Choice

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/charlieschoice-e1612397162104.jpg

349

466

chrispreperato

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/logo1.png

chrispreperato2021-02-03 04:59:582021-02-05 22:42:57Charlie’s Choice

The Guides

The Little Town In The Woods

Lost and Found

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/300056122-e1612410384314.jpeg

720

960

chrispreperato

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/logo1.png

chrispreperato2021-02-04 03:08:182021-02-05 22:41:35Cheesburger Falls

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/300056122-e1612410384314.jpeg

720

960

chrispreperato

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/logo1.png

chrispreperato2021-02-04 03:08:182021-02-05 22:41:35Cheesburger Falls http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IMG_8266-e1612409641903.jpg

948

1263

chrispreperato

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/logo1.png

chrispreperato2021-02-04 03:26:212021-02-05 22:40:35Tommy’s Hole

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IMG_8266-e1612409641903.jpg

948

1263

chrispreperato

http://historyoftheupperyough.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/logo1.png

chrispreperato2021-02-04 03:26:212021-02-05 22:40:35Tommy’s Hole